For years, I was unhappy with my oil paintings. I started my journey in 2019 as a beginner oil painter, with just a couple hobby classes under my belt, looking in awe at the works I saw online, in galleries, and museums. Unable to go to a full time atelier program, I took classes and workshops around New York City with top tier established artists. I developed my drawing skills, my understanding of light and form, anatomy, and structure.

However, something was always not quite right. My paintings seemed stuck. Even as my drawing skills improved, my eye evolved and I could see and feel the form and the structure, I was failing to express what I understood. My paintings would always fall a part.

I felt I was missing a serious oil painting foundation. Every oil painting class I’d taken discussed the same topics; value and color. Understanding the value scale and the color wheel. Get “the right value, right color, right shape”, and you got it. Simply “paint stripes in the right value towards the light”. I went to many different professors, different schools, and this was the most common foundational education, I heard it over and over again. Yet, something was not right. These ideas were not working. As I moved into my private practice, away from the classes, I stumbled upon, what I feel, is the most overlooked painting foundation, the Impasto.

Impasto is the building of paint in certain parts of the painting. Building more paint in one area and less paint in an other area. In working this way, one can almost feel like they are sculpting the painting, not just coloring in a drawing with value and color. This is a very important foundational technique, yet I rarely hear it being discussed in classes or online tutorials. Building impasto and varying paint quantity is crucial when working with oils. Without this technique, the painting can look dull and chalky, the painting may look flat, and it will be difficult to incorporate specificity and detail. Impasto is the heart of how oil paint functions, and if it was this overlooked in my education, I am writing this post in case others need this information as well.

Varying Paint Quantity Throughout the Painting

At a certain point of my practice, I found that my paintings were looking quite chalky. The common advice I found was to work on my color, my color mixing must be off. Yet, I found this wasn’t the whole story. Using a good quantity of paint in certain areas, and much less paint in other areas, while varying the amount of paint used throughout the main subjects and in each part of the painting makes the painting feel more unified and combats the chalkiness so often experienced by oil painters.

For example, when painting the background one should use much less paint than on the main subject. If there are multiple subject in your painting, those in the light, in focus, and of greatest importance, should have the most paint, allowing them to grab the attention. The more impasto used, the object will be seen as firmer, the less paint used, the object may feel more faded, or softer.

In Sargent’s Madame X, Sargent uses a large amount of impasto on the skin. One can see the intense structural effect in place, as he builds the form with paint. Building the form this way also ensures a more homogenous look to the skin tone. Alternatively, the background, hair and the dress are painted more transparently, using much less paint than on the figure. This variation is needed for the oil painting to work, and for the paint to shine. An oil painting cannot be painted without paint variation.

In addition, you can see the table has a stroke of thick paint in the front, and much less paint as it fades into the background. This allows the front of the table to come forward and the back of the table to recede, and is necessary for the spacial effect.

Building the Base: Sculpting the Form with Impasto

Probably the most important use of impasto is in developing the form. To me, oil painting is almost a mix of drawing and sculpting ( plus color, of course!). This is because oil paints are thick, they have some material to them, and this thickness plays an important role in how the oil paint is used. We are combining the use of this thickness (sculpting) with shadows and halftones (drawing). In oil painting, you can build the base of your structure like a sculptor, by adding more paint (impasto), as if you are adding clay. As the form turns away from you, you use less paint.

An example, one can build the protrusion of the forehead with heavy impasto, and using less paint as you reach the hairline. Or, Building the bulk of the forearm with heavy impasto, and using less paint as you reach the halftones and the background.

Building up the form with impasto, prior to being specific or adding details, will create the base of your form that is solid and three dimensional on which you can add subtlety and color variation. Sometimes, I feel like I am painting over a sculpture.

In the painting to the right, which is an example of an academic work from the Russian academy, you can see the entire painting is built up in a sculptural way. The painting uses impasto’s and heavy paint to describe the form, and lessens the paint when the form turns (the Lowe abdomen, under the breast). This is enough to create an impression of a figure.

Three Levels in Your Painting: High Impasto, Middle Impasto, Transparent

Within one subject, there should always be three levels of painting at work. Area’s of high impasto, area’s of middle impasto and areas of transparency. Within these three levels, there is also a range, a spectrum of paint application. For example, in a portrait, the shadows should be transparent, the halftones built with middle impasto and the lights built with high impasto, Areas that protrude more in the lights, and are particularly firm can be built with the highest level of impasto, such as the forehead and the cheekbones. This will allow the form to turn and the work to appear three dimensional. With oil, shifts in value are not sufficient, varying the paint in this way is essential to create the illusion of three dimensionality in the work. This is the sculptural element of painting, using the thickness of materials to develop the subject.

Not only should you think broadly with paint application (shadows, halftones, lights), but this train of thought should always be present. The neck, which sits further back then the face, needs to have enough paint to create form (if it is in the light), but must have much less paint then the head, which is protruding forward ahead of the neck. The eye sockets will have have much less paint (even if they are in the light) than the cheekbones, forehead, or nose, and the eyelashes and iris may even be transparent. This is the hierarchy which must always be considered when developing a painting. Constantly varying the paint application from transparent, to middle impasto, to high impasto, and something in-between.

Details work when they are painted on paint (the base)

Often teachers may tell you “don’t paint the details”, and “you will know when the details fit”. They may also say “keep it loose”, “my students paint too tight!” What do they mean by this? They are referring to the fact that their paintings tend to come together after the base is built. Once the form and three dimensionality is developed with enough paint, the smaller details and subtle variations begin to just “fit”.

While building the base, there is no point in developing subtle variation or detail, because it is a time to add more and more paint. This is also allows one to paint loosely, as the painting is developing, since things will likely be covered up. Many times, paint works best when it is painted on paint, thus once the thick impasto has been applied, the details and subtle variations will feel more effortless, as opposed to trying to add these details from the beginning.

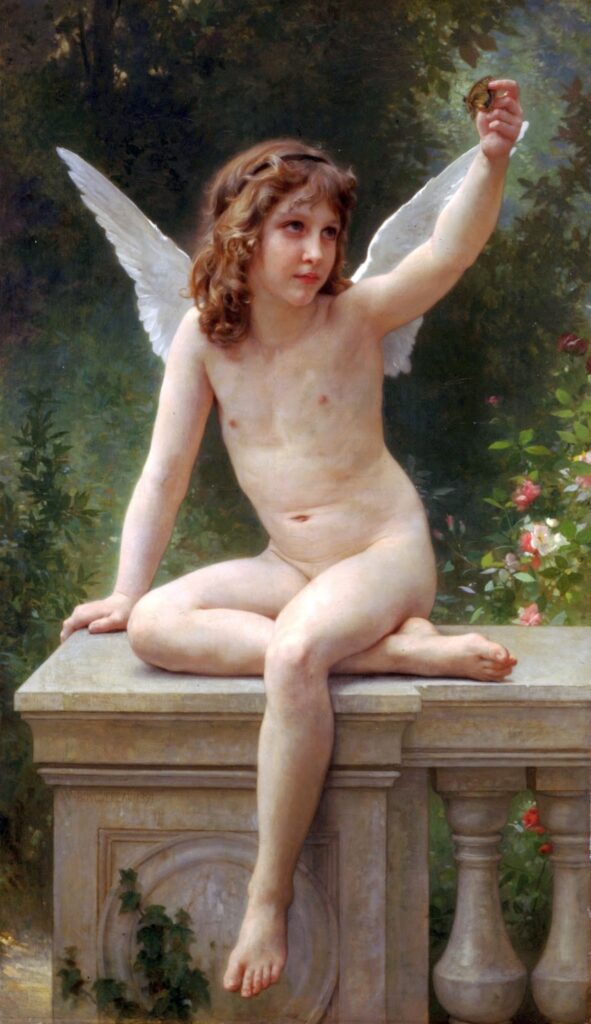

In Bouguereau’s painting to the right, one can see how much impasto has been built up to create the sculpture of the form, and only above this base did he begin to add subtle color changes, and more specific details to bring his painting to such subtle resolution.

I hope you have learned a little more about impasto and I hope this improves your work! The good thing is, I think this is the easiest foundational technique. Once you know it, you know it. Your hand will instinctively know when to add more or less paint the more you practice. Value and color can be more complex. With every painting one must see the value and color relationships, and even advanced painters can struggle and regret their choices. I believe this is exactly why this foundation is often overlooked in importance in classrooms, because unlike other elements of oil painting, it is not a life long struggle. Many artists who have been working for many years have probably forgotten when they do it, or when they learned it. Yet, as I said earlier, it is the heart of oil painting! This is how oil paint behaves, and how it must be applied in order to do what we want it to do. This is how representational paintings have been built for hundreds of years.

Remember, three levels of painting (transparent, middle impasto, high impasto), building the base, and the details “fit” when they are painted on paint. Happy Painting!